The RMS Carpathia – A Heroic Rescue

By the early hours of the morning on the 15th of April 1912, the Cunard Liner, RMS Carpathia had turned off her lights and settled down for the night. The steamer was on her regular trip between New York and Fiume (also now known as Rijeka) and when she left New York on the 11th of April, she had 125 first-class passengers, 65 second-class and 550 third-class passengers onboard.

It was a clear, cold night and earlier that day, there had been many wireless messages warning the ships sailing in the Atlantic of the presence of icebergs, which was not unusual for the time of year. The wireless operator on board, Harold Cottam aged just 21, decided to have one last listen to the radio before going to sleep. As he undressed, he heard general messages from Cape Cod, Massachusetts saying that the wireless operator on the Titanic was overworked conveying private passenger messages and greetings. Cottam takes the messages and contacts the Titanic. He receives a chilling response in return – ‘C.Q.D. S.O.S. Come at once. We have struck a berg.’

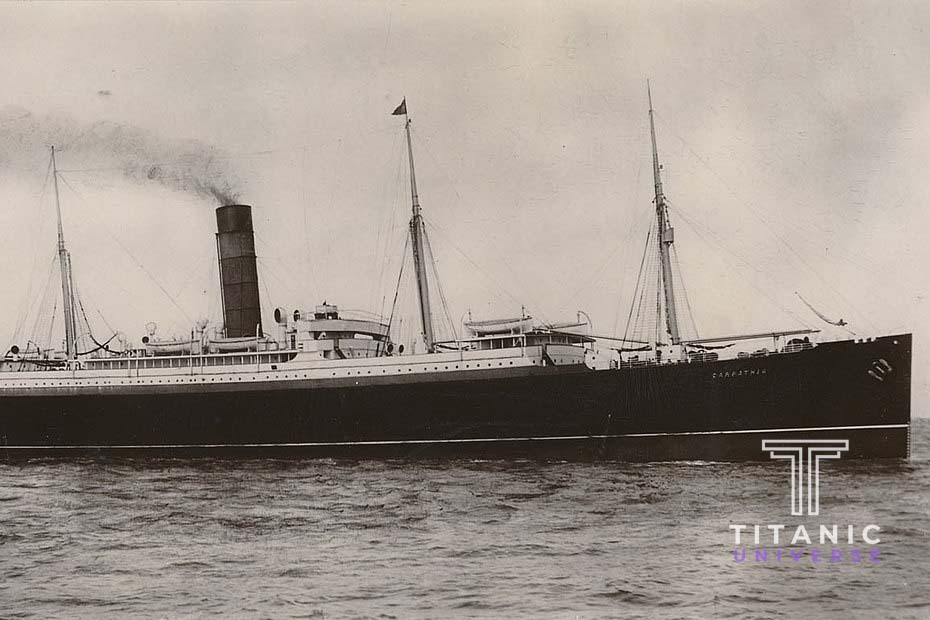

RMS Carpathia was built in 1902 by the Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson Company and was launched from Newcastle upon Tyne. Initially designed to transport immigrants between Europe and America, the maiden voyage of Carpathia took place on the 5th of May 1903 from Liverpool, bound for New York. In 1905, the Carpathia underwent a full refurbishment and was then able to provide comfortable accommodation for 100 first class, 200-second class and 2,250 third class passengers. The ship was renowned for having superior rooms for the third-class guest, with meals included in the fare. By 1912, she had made many transatlantic crossings between the Mediterranean and America

After hearing the shocking message on the wireless, Cottam rushed to tell the senior officer on watch on the deck. He is sceptical of the news that Titanic, the brand new unsinkable ship on its maiden voyage, is in trouble. Cottam then wakes the Captain, Arthur Rostron, who immediately senses the seriousness of this news. He calls for all hands on deck and they plot the course to Titanic’s last known position, which is about 60 miles away.

Rostron then ordered all the hot water, heating and steam to be cut off from the passenger cabins to help the ship increase its top speed from 14.5 knots to 18 knots. He gathered all available sailors to watch closely for icebergs as they approached the ice field. In addition, he also requested the crew to make ready the lifeboats, the stewards and chefs of the ship to prepare hot drinks and soup, blankets and warm clothes to be found and the dining rooms to be turned into makeshift hospitals. They thought that they may have to rescue all of the 2000 passengers the Titanic carried and these preparations had to be made quietly so that the Carpathian’s own passengers would not wake up and be panicked. Rostron estimated it would take four hours to reach the Titanic but would that be quick enough to help?

The Carpathia carried on through the dark, cold night, narrowly missing icebergs and looking for any sign of the stricken Titanic. Rostron was a deeply religious man and he was said to be seen praying for a safe path through the difficult waters. Looking back on this traumatic night, Rostron declared, ‘I can only conclude another hand than mine was on the helm.’ At around 4 am, the Carpathia approached the site and the ship launched green flare rockets to alert the survivors of their approaching presence.

Tragically, the Titanic had sunk an hour and a half before the RMS Carpathia arrived. They found the survivors, freezing cold and huddled in the lifeboats, shocked and traumatised by what they had witnessed. The crew and passengers of the Carpathia then spent the next four and a half hours loading the 705 survivors onto the ship and they were given blankets, coffee and warm clothes. The passengers of the Carpathia tried to help in any way they could and took time to try and console the mostly distressed widows who had come on board. The ship then sailed through the wreckage to see if any more survivors could be found, but sadly, this quest was unsuccessful.

RMS Carpathia then sailed onto New York, arriving on the morning of the 18th of April. The ship was besieged by reporters and crowds, trying to find out the details of what had occurred out in the dark Atlantic ocean. Captain Rostron and the rest of the crew were hailed as heroes and Rostron was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest honor in the United States of America and knighted by King George V of Great Britain.

After the heroic rescue, the Carpathian returned to its usual Mediterranean route until the outbreak of World War I. During the war, the ship was used to move American and Canadian forces to Europe. On the 15th of July 1918, the Carpathia was travelling in convoy en route to Boston with 57 passengers and 166 crew on board. Unfortunately, the ship was hit by two torpedoes and rapidly began taking on water. Whilst the crew were preparing the lifeboats, a third torpedo struck and killed five crew members. The orders came to abandon ship and two and half hours later, the Carpathia sadly sank. The rest of the crew and passengers were rescued by the HMS Snowdrop. It was a tragic and untimely end to a ship that had performed such a heroic act and had saved so many lives.