On April 15, 1912, the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and began a slow sink into the frigid waters of the North Atlantic. Aboard this majestic ship was over 2200 people, who were both passengers and crew, but the danger was not immediately known except for a handful of men on the bridge. What was so hard to believe was the fact that the Titanic, who was supposed to the biggest, grandest, and unsinkable, had struck an iceberg, and was slowly dying. The decks of the mighty ship seemed just as strong as ever, but down below those decks, the ship was being overtaken with gallons of freezing cold water. However, was it just the bridge crew that new Titanic was in trouble, or did White Star officials back in New York City know that their brand new ship was in danger?

On April 15, 1912, the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and began a slow sink into the frigid waters of the North Atlantic. Aboard this majestic ship was over 2200 people, who were both passengers and crew, but the danger was not immediately known except for a handful of men on the bridge. What was so hard to believe was the fact that the Titanic, who was supposed to the biggest, grandest, and unsinkable, had struck an iceberg, and was slowly dying. The decks of the mighty ship seemed just as strong as ever, but down below those decks, the ship was being overtaken with gallons of freezing cold water. However, was it just the bridge crew that new Titanic was in trouble, or did White Star officials back in New York City know that their brand new ship was in danger?

Titanic Begins to Send Out Call For Assistance

The clock on the bridge read 11:40 pm when the RMS Titanic scraped her right side along a huge, frozen, iceberg. First Officer William Murdoch had ordered Quartermaster Robert Hitchens to turn the ship out of the way, but it was too late. Once the Titanic had fish tailed around the iceberg, Captain Smith was on the bridge in seconds to find out what had happened. Murdoch explained to him about trying to steer out of the way, and how he had closed the watertight doors after the collision with the iceberg. Smith saw the list the ship already had, and immediately called for Thomas Andrews, and the ship carpenter, to assess the damage caused by the iceberg. It was Thomas Andrews that knew every inch of the Titanic, and it was he who knew the best places to check and see exactly what the iceberg had done. Andrews had been getting reports about where the ship was flooding, and once glimpse into the mailroom told him all he needed to know. With a grim face, Andrews returned to the bridge to inform Captain Smith that the Titanic had an hour, perhaps two, but not much more beyond that. At that moment, Smith knew his ship was doomed, and he had the lives of 2200 people in his hands. He went from the bridge to the radio room, where he faced his two radio operators, and told them to start sending the call for assistance. The two young men looked at each other, and then leapt into action using both the “CQD” and “SOS” radio signals. The Titanic was sinking, and she had very little time left.

The Telegrams Sent by Jack Phillips

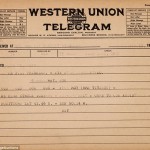

Imagine the tremendous amount of pressure that these young men faced as the Titanic sank lower and lower into the water? The passengers, at first, were unaware of what was really happening, but as the minutes ticked by, the slow realization that they were about to die must have come to the passengers becuase the mood on board began to change. Jack Phillips had one goal, and that goal was to make sure that someone out there knew that the Titanic had struck an iceberg and was sinking fast. However, while it is unclear how many messages Jack Phillips sent was unclear, but one that he sent was recently uncovered.

The telegrams that Jack Phillips sent were scattered upon the water like leaves, and there are many ships that got them including Titanic’s sister ship, Olympic. However, what Phillips did not know was that there were people in New York City who were also able to pick up the signals that the wireless room was sending. Because there were so many messages going back and forth across the ocean, it was difficult to figure out which was the truth. The one telegram that Jack Phillips sent would become quite an important one because it may reveal the answer to the question as to whether the White Star Line offices back in New York City were aware of what was going on in the middle of the North Atlantic in the dead of night on April 15th, 1912.

Did the White Star office know that their brand new ship was in trouble thanks to Jack Phillips? Did they lie to the public when asked of the Titanic situation? These are questions that Titanic enthusiasts have been asking for a long time now, and this very special telegram just may reveal the answer to that very question.